Crete's history is long and epic, spanning millennia and marked by advanced ancient civilisations, foreign conquests, and heroic struggles. This island has been a centre of human activity since at least 7000 BC, with waves of influences leaving their mark. Here's an immersive journey through Crete's rich history – from the mysterious Minoans to the modern era:

Minoan Civilisation (c. 3000–1100 BC)

Our story begins with the Minoans, the people of Bronze Age Crete, who established Europe's first advanced civilisation. By around 2000 BC, grand palaces were built at Knossos Palace, Phaistos, Malia Palace, and Zakros Palace. These were not just royal residences, but also administrative and religious centres for the island. The Minoans developed a vibrant culture known for its energetic art and monumental architecture. They had a form of writing (Linear A, still undeciphered) and extensive trade networks across the Aegean and beyond.

'Knossos Palace' - Attribution: Shadowgate

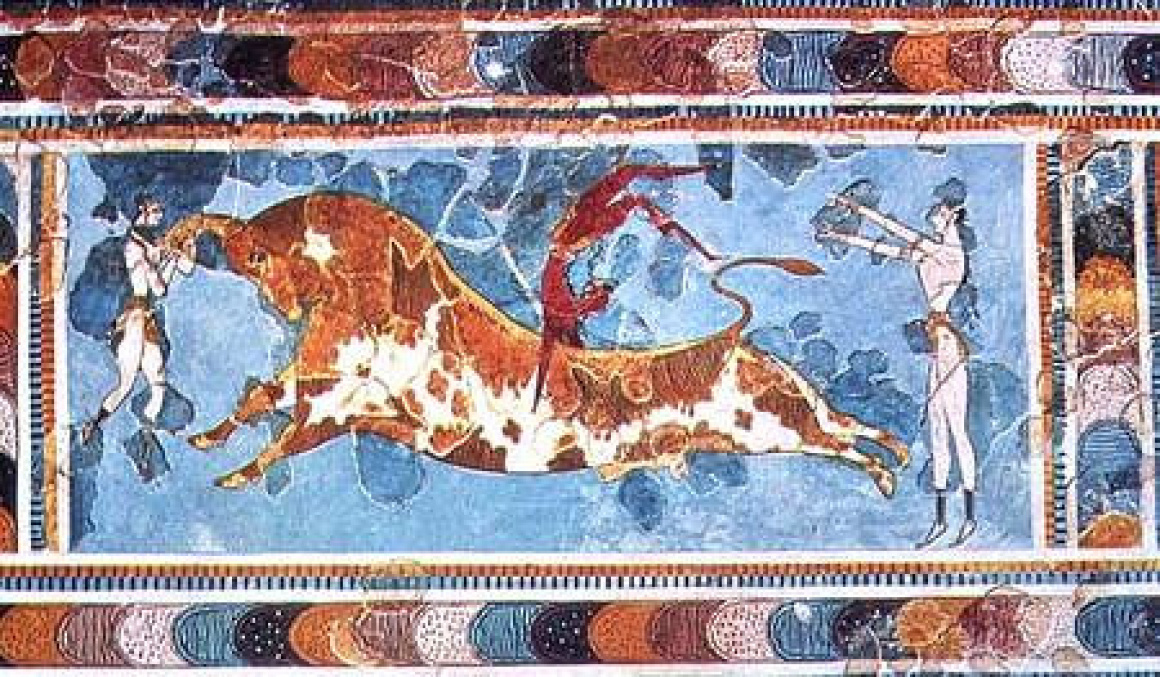

'Knossos Palace' - Attribution: ShadowgateAt the famous Knossos Palace, which you can visit today, you'll see the sophistication of the Minoans on full display: multi-storey buildings, colourful frescoes of dolphins and dancers, storerooms once filled with olive oil and wine, and even evidence of one of the earliest plumbing systems in the world (yes, the Minoans had flushing toilets and complex drainage over 3,500 years ago!). The iconic Bull-Leaping Fresco from Knossos depicts a ritual where youths vaulted over a charging bull – reflecting the Minoans' deep religious symbolism and perhaps the origin of the myth of the Minotaur.

'Dolphins' - Attribution: Ania Mendrek

'Dolphins' - Attribution: Ania MendrekMinoan Crete was likely a thalassocracy (a sea power), relatively peaceful at home (not much evidence of city walls) but dominant at sea. The eruption of Thera (Santorini) around 1600 BC and subsequent tsunamis might have devastated Crete, weakening the Minoans. By around 1400 BC, control of Crete had shifted to Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland, who adapted the Minoan script into Linear B (an early form of Greek). The Minoan era left an indelible legacy – the term Labyrinth comes from the Minoans (the palace of Knossos with its many rooms likely inspired the labyrinth myth, and the double-axe labrys was a key symbol). Visiting Crete's Minoan sites today, like Knossos or Phaistos, you walk in the footsteps of a civilisation that laid the groundwork for later Greek culture.

Ancient Greek and Roman Period (c. 1100 BC – 824 AD)

After the Minoan decline, Crete saw the rise of city-states and integration into the classical Greek world. By the 8th century BC, Dorian Greeks had settled in Crete. Cities like Knossos (which remained inhabited long after the palace's glory days), Gortyna, Lato, and Polyrrhenia emerged. Crete is even mentioned in Homer's Odyssey. The island's strategic position made it somewhat apart from mainland affairs, but Cretans did participate in wider Greek events occasionally (though famously, Crete did not send ships to the Trojan War, as its own king Idomeneus had a different saga).

'Gortys or Gortyn (Crete, Greece): archaeological site with Roman Odeon' - Attribution: Marc Ryckaert (MJJR)

'Gortys or Gortyn (Crete, Greece): archaeological site with Roman Odeon' - Attribution: Marc Ryckaert (MJJR)During the Hellenistic period, Crete had a reputation for skilled archers and mercenaries. City-states on Crete often feuded with each other or formed leagues. Then came the Romans: In 67 BC, Crete was conquered by Rome after fierce resistance led by the Cretan leader Lasthenes. The Romans merged Crete with Cyrenaica (modern Libya) into a single province. The provincial capital became Gortyn in south-central Crete. Gortyn flourished under Rome – it's famous for the Gortyn Law Code, an extensive inscription of civil law dating back to the 5th century BC, which you can still see carved in stone on site. Gortyn's ruins (including a Roman amphitheatre and the basilica of St. Titus) highlight that era. Under Rome, Crete enjoyed stability and was Christianised early, Apostle Paul even mentioned Crete in the Bible (Letter to Titus). By the end of antiquity, Crete was part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine Empire) as it split from Rome.

'Cathedral of Agios Titos, Plateia Agiou Titou, Heraklion, Greece' - Attribution: w_lemay

'Cathedral of Agios Titos, Plateia Agiou Titou, Heraklion, Greece' - Attribution: w_lemayByzantine and Arab Era (824–961 AD)

As the Western Roman Empire fell, Crete remained under the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman) initially, from the 4th to early 9th century. In this period, the island was largely Christian Greek in culture, dotted with early churches. However, a dramatic turn came in 824 AD: Andalusian Arabs (Moors) invaded and seized Crete, establishing an independent Emirate of Crete. They made Ḥandāq (today's Heraklion) their fortified capital, renaming it Rabdh al-Khandaq (“Castle of the Moat”) due to the ditch fortifications – the name “Candia” (used by Venetians later) stems from that. During the 136 years of Arab rule, Crete became a notorious pirate haven, Arab pirates from Crete raided Byzantine shipping and even sacked parts of Greece. This era left fewer architectural remains (aside from some fort ruins) but had a lasting impact – a portion of the population converted to Islam, and the island's prosperity during this emirate was significant due to piracy and trade.

The Byzantine Empire did not sit idle. After several failed attempts, the Byzantines under Emperor Nikephoros Phokas recaptured Crete in 961 AD, storming Heraklion in a bloody campaign. Crete returned to Byzantine control, and efforts were made to re-Christianise and re-Hellenise the island. The second Byzantine period (961–1204) saw the building of churches (some with beautiful frescoes that survive in villages) and relative peace, though pirate threats remained. Crete's location always made it a coveted stepping stone between continents.

Venetian Period (1204–1669)

The Fourth Crusade in 1204 brought major changes to the Greek world. Venice, a maritime superpower, gained control of Crete in the aftermath of that crusade. Thus began over four centuries of Venetian rule, a period that deeply influenced Cretan architecture, culture, and society. The Venetians called Crete the “Kingdom of Candia,” with Candia (Heraklion) as the capital. They established a feudal system, parceling out lands to Venetian nobles, and built impressive fortifications to secure the island. Many of Crete's most striking historical landmarks date from this era. For example, the Venetian Walls of Heraklion – the massive city walls and bastions you can still walk on – were built to repel Ottoman invasions. The pretty lighthouses in Chania and Rethymno harbours, the Fortezza of Rethymno (a star-shaped fortress overlooking the town), and castles like Frangokastello in the south were all Venetian works. The old towns of Chania and Rethymno especially showcase Venetian architecture – elegant loggias, arched doorways, stone mansions, and fountains. In fact, the urban layout of those towns today, with narrow lanes and two-storey houses, is largely a Venetian legacy.

'Frangokastello' - Attribution: Mavroudis Kostas

'Frangokastello' - Attribution: Mavroudis KostasCretan society during Venetian rule was a tale of two groups: the Venetians (Catholic rulers) and the Cretan Greeks (Orthodox populace). There were periodic revolts by Cretans against heavy taxation and Catholic influence. One famous revolt was led by a Cretan hero nicknamed “Skordilos”, another major uprising (the Revolt of St. Titus in the 1360s) briefly established a commune in Candia. Over time, a unique Cretan Renaissance flourished in the 16th–17th centuries – Crete became a thriving centre of arts and literature, blending Venetian and Greek influences. This era produced the famous artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, who was born in Crete (in 1541) and trained in the Cretan school of icon painting before moving to Spain. The island also produced significant literature, like the epic poem “Erotokritos” by Vitsentzos Kornaros around 1600, a cornerstone of modern Greek literature.

Venetian rule was tested by the rising Ottoman Empire. Starting in 1645, the Ottomans invaded Crete, they quickly took most of the island but Candia (Heraklion) held out in a siege for 21 years – one of the longest sieges in history. Finally, in 1669, Heraklion fell after a negotiated surrender by the Venetians (the commander Francesco Morosini handed over Candia to the Ottomans). Thus ended Venetian Crete after 465 years. The Venetians managed to keep a couple of island fortresses (Souda, Gramvousa, Spinalonga) until 1715, but essentially Crete became Ottoman. Venetian legacy, however, remained in the architecture, in some Venetian words in the Cretan dialect, and in the Cretans' continued connection to Western Europe in terms of art and learning.

Ottoman Rule and Independence (1669–1898)

The Ottoman period in Crete was another chapter of change and turmoil. Under the Ottomans, Crete was ruled by Pashas (governors) and many Venetians and locals fled after the conquest. A portion of the Cretan population converted to Islam over time (these converts were called “Turkocretans”, though ethnically they were Cretan). The Ottomans left their mark with Islamic architecture – you'll notice historic mosques in Cretan cities, often conversions of earlier churches. For example, the Janissaries Mosque at Chania's harbour (now an exhibition hall) and the Valide Sultana Mosque in Rethymno, and several Turkish fountains and hamams (bathhouses).

Life for Cretan Christians under Ottoman rule was marked by heavy taxes (like the harach poll tax) and second-class status, leading to frequent rebellions. The Cretans never stopped yearning for freedom (Eleftheria). Notable revolts include Daskalogiannis's rebellion in 1770 in Sfakia – Daskalogiannis is a legendary figure who met a tragic end (skinned alive) for rising against the Turks. The 19th century saw continuous unrest. During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), Cretans also rebelled, but Crete did not achieve liberation then and was given by the Great Powers to Egyptian control for a period (as Muhammad Ali of Egypt helped the Ottomans quell the revolt). After being returned to direct Ottoman rule, the uprisings continued, one of the largest was the Great Cretan Revolt of 1866–69, during which the Holocaust of Arkadi Monastery occurred – hundreds of rebels and civilians blew themselves up with gunpowder at Arkadi Monastery rather than surrender to Ottoman forces, making it an enduring symbol of resistance.

'This is a photo of a monument in Greece identified by the ID' - Attribution: C messier

'This is a photo of a monument in Greece identified by the ID' - Attribution: C messierBy the late 19th century, the Cretan question became an international issue. Ottoman rule was weakening and Christian powers (Britain, France, Russia, Italy) intervened. A final massive revolt in 1897, combined with the intervention of the European powers (who landed troops in Crete), led to the end of Ottoman rule. In 1898, Crete was granted autonomy as the Cretan State under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire but effectively under international protection. A young Greek prince, George, became the High Commissioner, and a local Cretan hero, Eleftherios Venizelos, emerged as a political leader. Venizelos (born in Chania, 1864) had been a key figure in the independence movement and would soon rise to prominence, he is credited with skillfully guiding Crete's politics in this era.

Finally, in 1913, Crete achieved its long-desired union with the Kingdom of Greece. After the Balkan Wars, the Ottoman Empire relinquished all claim to Crete. On December 1, 1913, the Greek flag was raised at the Firkas Fortress in Chania in a ceremonious celebration with Venizelos (by then Prime Minister of Greece) and King Constantine in attendance. Crete was now proudly part of the modern Greek state.

20th Century – World Wars and Modern Crete

Crete's modern history as part of Greece saw new challenges and contributions. The islanders, known for their bravery, took part in all major Greek conflicts. During the Balkan Wars and World War I, Cretan fighters were active. Eleftherios Venizelos, the famed Cretan statesman, served multiple terms as Prime Minister of Greece, leading the country through turbulent times and greatly expanding Greece's territory (he's often called the “Maker of Modern Greece”).

World War II brought the Battle of Crete in May 1941 – a dramatic and significant chapter in Crete's history. In brief, German paratroopers invaded Crete, and Cretan locals, alongside Greek and Allied (British, Australian, New Zealander) troops, mounted a fierce resistance. Crete fell to Nazi occupation, but the Cretan resistance remained very active throughout the war, at great cost to local villages.

After WWII, Crete shared in Greece's ups and downs – including economic migration (many Cretans moved to Athens or overseas in the 1950s–60s), but also benefited from the growth of agriculture (olive oil, grapes) and eventually tourism. By the late 20th century, Crete transformed into one of Greece's more prosperous regions, with improved infrastructure and education (the University of Crete and other institutions were established).

Today, modern Crete is a dynamic blend of old and new: cutting-edge research centres in Heraklion and lively student cities, but also age-old farming traditions still alive in villages. Cretans are keenly aware of their history, they preserve their heritage through museums, restored sites, and cultural festivals. When you visit Crete, you don't just get a tan on the beach – you get a profound sense of how much this island has seen and endured through the ages. From the mythic tales of King Minos to the heroism of WWII resistance fighters, Crete's story is as dramatic as the landscapes that frame it.