Crete's architecture is a fascinating palimpsest – layer upon layer of different eras and influences, all coexisting on this island. From the remnants of ancient palaces to Byzantine monasteries, Venetian fortresses, Ottoman mosques, and charming Greek island homes, Crete's built environment tells the story of its past. Exploring towns and sites in Crete, you'll encounter a diverse array of architectural styles often within footsteps of one another. Let's take a deep dive into the architectural heritage of Crete:

Minoan and Ancient Architecture

The oldest architectural wonders in Crete date back to the Minoan civilisation (Bronze Age). The Minoan palaces such as Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Zakros were astonishingly advanced for their time (circa 2000–1500 BC). They weren't castles with big walls – interestingly, Minoan palaces lacked defensive walls, suggesting a period of relative peace or naval security. Instead, they were expansive complexes with dozens of rooms arranged around central courtyards. These palaces boasted sophisticated features: multi‐story buildings, grand staircases, light‐wells to bring daylight inside, and elaborate storage magazines with pithoi (giant clay jars). One striking aspect is the plumbing and drainage – Knossos had an intricate system of terracotta pipes and drains, even including flushing toilets, which was millennia ahead of its time. The distinctive Minoan columns (painted red or black) taper downward – wider at the top, narrower at the bottom, in contrast to later Greek columns.

'Minoan Palace at Knossos. North entrance.' - Attribution: Stegop

'Minoan Palace at Knossos. North entrance.' - Attribution: StegopBeyond the palaces, ordinary Minoan towns – like the excavated town of Gournia in east Crete – reveal well-planned streets and houses with stone foundations. As time moved forward, Crete in the classical Greek and Hellenistic periods adopted typical Greek city architecture with agoras (marketplaces), temples, and theatres. Although not many ancient Greek temples remain, one notable site is Lato, a Dorian city in Lassithi where you can see the layout of a Greek city-state in ruins. The Roman period left behind aqueducts, bathhouses (thermae), and a large amphitheatre in Gortyna, as well as impressive Roman cisterns near Kastelli Kissamou. In Eleftherna, Hellenistic houses and a later Roman villa have been uncovered, showcasing beautiful mosaic floors.

Venetian Architecture (13th–17th centuries)

Arguably, the most visually striking architecture in Crete comes from the Venetian era. When the Venetians took over in 1204, they heavily fortified the island and either built new cities or expanded the old ones. They introduced Gothic and Renaissance architectural styles from Italy. Key elements of Venetian architecture in Crete include:

- Forts and Walls: Massive fortifications like the Fortetsa (Fortezza) of Rethymno, a star-shaped fortress on a hill, or the huge walls of Heraklion (Candia) with bastions (e.g. Martinengo Bastion where Kazantzakis is buried) and a giant moat. These walls were engineering marvels of the 16th century, designed to withstand cannon fire. Chania’s old town too had walls (some sections still visible near the harbour and west Old Town). Many smaller coastal forts dot Crete – Gramvousa islet has a Venetian fort, Spinalonga island fort (later used by Ottomans too), Frangokastello in the south (a lonely castle on a plain built to subdue Sfakia region).

- Harbours and Arsenals: The Venetians were sea traders, so they invested in harbours. Chania’s Venetian harbour with its picturesque lighthouse (built in the 16th century, modified by Egyptians in the 19th c) is a prime example. Next to Chania’s harbour you see the arsenals (Neoria) – these were vaulted shipyards where they repaired galleys. These long stone boathouses still stand in Chania (some now house exhibition spaces or restaurants). In Heraklion, you can also see several Venetian arsenals by the port, and the Koules Fortress at the harbour entrance – a squat, thick-walled sea fortress that guarded the entrance, bearing the Lion of St. Mark crest above its gate. Rethymno’s harbour also retains a smaller version of these features (lighthouse and quay).

- Public Buildings and Loggias: The Venetians constructed elegant civic buildings. In Heraklion, don’t miss the Venetian Loggia, a beautiful arcaded building (with round arches and Doric columns) that was essentially a gentlemen’s club / city hall for Venetian nobles. It’s been restored and today serves as the Town Hall. Nearby, the Morosini Fountain (Lion’s Fountain) in Heraklion (built 1628) is a classic Venetian centerpiece for a square, with four lions supporting a basin – it still flows with water and is a popular meeting point. In Chania, the Janissaries Mosque ironically is an Ottoman building but uses a Venetian-era base; however, Chania’s Governor’s Palace (Palazzo) was lost in WWII bombings. Rethymno has a well-preserved Rimondi Fountain (three lion heads spouting water, 1626) and the Venetian Loggia of Rethymno – now an art shop, this small loggia has three elegant arches facing the street.

- Residential Architecture: Venetian houses often had internal courtyards, external staircases, and wooden balconies (some of which were later additions in Ottoman times). In Chania and Rethymno Old Town, you’ll wander through narrow streets with tall two- or three-story houses that have stone doorframes with Venetian Gothic carvings or coats of arms, and overhead, charming wooden “sachnisia” balconies (projecting covered balconies) which became common in late Venetian/Ottoman transition. Many houses show this blend – the ground floor with stone and Venetian arches, the upper floor with Turkish-style latticed woodwork. The street plan of the old towns, with labyrinthine alleys, is largely a product of the Venetian period (adapted to medieval needs). There are still some palazzos (noble mansions) – for example, in Heraklion the Palace of the Venetian Duke (Ducal Palace) is gone, but in Chania, some grand homes in the Topanas district hint at past nobility.

'Chania Venetian Harbour' - Attribution: Miguel Virkkunen Carvalho

'Chania Venetian Harbour' - Attribution: Miguel Virkkunen CarvalhoVenetian influence extended to finer details as well: the Cretan dialect adopted Italian words, and architecturally, you can find Latin inscriptions on fort gates or the winged Lion of Saint Mark carved above castle entrances, as seen at Koules Fortress in Heraklion or on city gates like the “Chanioporta” in Heraklion's walls.

'This is a photo of a monument in Greece identified by the ID' - Attribution: C messier

'This is a photo of a monument in Greece identified by the ID' - Attribution: C messierOttoman Architecture (17th–19th centuries)

When the Ottomans assumed control, they converted existing structures and built new ones to suit their needs. Many churches were transformed into mosques, so you might notice older churches in Crete sporting minarets – even if today some of them have become museums or lie in ruins. In Rethymno, the Neratze Mosque – originally a Venetian church – still stands with the city's highest minaret, although today it serves as a music conservatory, the minaret remains a reminder of its past. In Chania, the Hünkar Mosque (or Sultan's Mosque) on Halidon Street was once the Venetian Cathedral before being converted into a mosque and later an Orthodox church. Often, the Ottomans simply added minarets to existing structures, and while some have fallen into disrepair, many slender minarets continue to define the skyline. New Ottoman mosques were also built, such as the Janissaries Mosque at Chania harbour (notable for its domed roof and absence of a minaret, built in 1645 shortly after the conquest). In Heraklion, remnants of mosques like the Valsamaki (Kara Musa Pasha) Mosque can be found, sometimes repurposed as stores or museums. Public fountains, often with marble and Arabic inscriptions, and the introduction of bathhouses (hamams) further testify to the Ottoman contribution to Crete's urban landscape. In Rethymno, a 17th-century hamam on Radamanthyos Street and the remains of the “Vizir Tzami” hamam in Heraklion (now part of a modern café) are prime examples of this legacy.

'Sandy Hania' - Attribution: currybet

'Sandy Hania' - Attribution: currybetThe Ottomans also repurposed former Venetian mansions and built new homes in their urban style – characterised by protruding upper floors in wood and the now typical sachnisia balconies. Walking through Chania or Rethymno's backstreets, you'll encounter these charming bay windows, which allowed the women of the house to observe street life discreetly, in keeping with Ottoman customs. In the countryside, small fortified “koules” towers built during the late Ottoman era (19th century) can still be seen as vestiges of a turbulent past.

'P8198965' - Attribution: taver

'P8198965' - Attribution: taverReligious Architecture

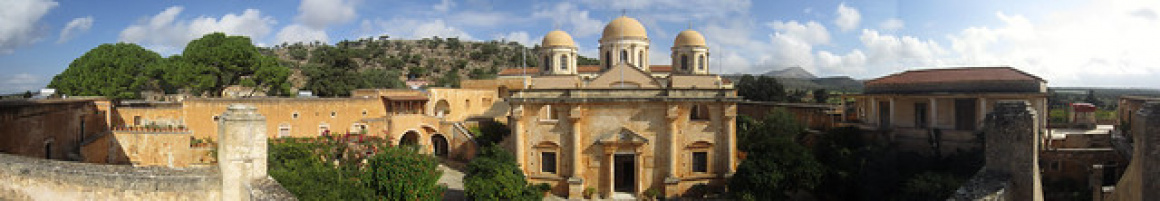

Crete's religious buildings offer another lens into its layered history. Orthodox churches and monasteries typically feature simple stone exteriors with a single nave or a cruciform shape and interiors adorned with frescoes or icons. A prime example is the Arkadi Monastery near Rethymno, originally built in the 16th century with a beautiful Venetian baroque church façade, its fame grew following the tragic events of 1866. Other examples include the Monastery of Preveli and Agarathos Monastery near Heraklion, which display Venetian-influenced stone carvings around their doors. In contrast, older establishments such as Katholiko Monastery on the Akrotiri peninsula or Toplou Monastery in east Crete have fortress-like features with thick walls and narrow windows, designed to withstand pirate raids and invasions.

'Crete' - Attribution: claudia.schillinger

'Crete' - Attribution: claudia.schillingerCatholic (Latin) churches from Venetian times were mostly converted to Orthodox churches or destroyed over time. However, in Chania, the Catholic Church of St. Francis survived, today it houses the Archaeological Museum of Chania, allowing visitors to appreciate the Gothic arches of its former structure.

'Archaeological Museum of Chania, Crete, Greece' - Attribution: Bernard Gagnon

'Archaeological Museum of Chania, Crete, Greece' - Attribution: Bernard GagnonModern and Vernacular Architecture

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Crete gained autonomy and eventually joined Greece, new architectural styles emerged. Neoclassical buildings began to appear in the cities – for example, in Heraklion, the Archaeological Museum building (dating from the 1930s) and public buildings or schools in Agios Nikolaos and Chania reflect the symmetry and columns typical of that era in Greece. Chania, which once served as the capital of Crete, is home to several elegant neoclassical government buildings and houses in districts such as Halepa, where grand mansions like the former French School (now part of the Technical University) still stand.

At the same time, the vernacular architecture in the villages continued to be humble and functional: whitewashed stone houses with flat or tiled roofs, thick stone walls to insulate from heat, and inner courtyards with grapevines. In the mountains, many homes were built partially underground or into slopes for natural insulation. Villages like Kritsa, Margarites, and Vamos allow you to stroll among traditional village homes – some lovingly restored by residents or expats – featuring small windows, outdoor staircases leading to upper terraces, and auxiliary outbuildings often housing ovens or wine presses. The importance of courtyard life is evident, with many homes concealing lovely inner courtyards complete with gardens or wells shielded by high walls, a design tradition that dates back to Venetian and Ottoman times.

'Kritsa Crete_26' - Attribution: George M. Groutas

'Kritsa Crete_26' - Attribution: George M. GroutasIn modern times, while much architecture is utilitarian – as seen with the 1970s and 80s concrete flat blocks, in the cities – there is a growing trend to revive traditional aesthetics especially for tourism. Boutique hotels are being created in old Venetian houses and new villas built in the style of traditional stone homes. Even resort architecture from the 80s and 90s is evolving, with newer constructions striving to blend with the landscape using stone facades, earth-tone colours, and low-rise layouts.

Notable Architectural Sights by City

Crete’s architecture reflects its layered history, shaped by Venetian, Ottoman, and modern influences. Across the island, you’ll find grand fortresses, elegant neoclassical homes, hidden Ottoman fountains, and even traces of Minoan civilisation. Some of the most notable architectural sights by city, town, and village are:

Heraklion

The capital of Crete boasts a fascinating mix of Venetian, Ottoman, and modernist influences. Highlights include the impressive Venetian walls and Koules Fortress, which once guarded the city’s harbour, and the elegant Venetian Loggia, now serving as the Town Hall. The Morosini Fountain, a landmark in Lion Square, showcases intricate Venetian-era stonework.

Religious sites include the historic Saint Titus Church, which has served as both a mosque and an Orthodox church, and the grand Agios Minas Cathedral, one of the largest churches in Greece. Hidden within the bazaars, Ottoman-era fountains add to the city's layered history. For a modern contrast, the Archaeological Museum stands out with its striking mid-20th-century design.

'Agios Minas Cathedral, Plateia Agiou Mina, Heraklion, Greece' - Attribution: w_lemay

'Agios Minas Cathedral, Plateia Agiou Mina, Heraklion, Greece' - Attribution: w_lemayChania

Chania’s old town is a stunning blend of Venetian, Ottoman, and neoclassical architecture. The picturesque Old Harbour is home to the iconic lighthouse and the Venetian arsenals, while the imposing Firkas Fortress stands guard at its entrance. The districts of Splanzia and Topanas are filled with winding alleys, where Venetian doorways and Ottoman-era wooden balconies create a unique atmosphere.

Among its notable religious sites are the Mosque of Janissaries, a striking example of early Ottoman architecture, the Catholic Church of St. Francis (now housing the Archaeological Museum), and the Orthodox Cathedral Trimartyri, built in 1860. Just outside the old town, the neoclassical quarter of Halepa is home to elegant mansions, including the House of Eleftherios Venizelos, the residence of one of Greece’s most influential statesmen.

'Orthodox Cathedral in Chania, Crete, Greece' - Attribution: Doris Antony, Berlin

'Orthodox Cathedral in Chania, Crete, Greece' - Attribution: Doris Antony, BerlinRethymno

Rethymno’s architectural charm lies in its well-preserved mix of Venetian and Ottoman influences. The hilltop Fortezza castle offers breathtaking views, while the Rimondi Fountain stands as a graceful Venetian relic. The Neratze Mosque, originally a church, features a towering minaret and now serves as a music hall.

The historic Venetian Loggia and the Great Gate (Porta Guora), once the city’s main entrance, reflect the grandeur of Rethymno’s past. Wandering through streets like Vernardou and Arkadiou, visitors can admire beautifully preserved Venetian-Ottoman townhouses.

'Rimondi Fountain Rethymnon' - Attribution: George M. Groutas

'Rimondi Fountain Rethymnon' - Attribution: George M. GroutasSmaller Towns

- Agios Nikolaos, once a small fishing village, has fewer historical buildings but boasts a picturesque lake and a port lined with neoclassical structures.

- Sitia features remnants of a Venetian castle, Kazarma, along with a charming neoclassical quarter.

- Ierapetra retains an Ottoman mosque and a small Venetian fortress on the waterfront.

- Hersonissos and Malia are largely modern tourist towns, though near Malia, visitors can explore the fascinating remains of a Minoan palace.

'Crête : Agios Nikolaos' - Attribution: DaffyDuke

'Crête : Agios Nikolaos' - Attribution: DaffyDukeVillages

- Spili is known for its Venetian fountain adorned with multiple lion-head spouts and well-preserved houses.

- Archanes stands out with its beautifully restored neoclassical houses painted in pastel colours, making it a model traditional village.

- Vamos showcases authentic folk architecture and has several renovated historic inns.

- Margarites is famed for its stone and clay-plastered homes, as well as its traditional pottery workshops.

- Anogia, though largely rebuilt after WWII, maintains the stone architecture characteristic of mountain villages.

- Mochlos retains a simple, traditional fishing village layout with an unspoilt charm.

'Mochlos village' - Attribution: exfordy

'Mochlos village' - Attribution: exfordyPreserving the Heritage

Crete has taken significant steps to preserve its architectural heritage, a crucial draw for tourism. Historic monuments, such as the partially reconstructed Knossos Palace help visitors visualise the past, even as debates over restoration continue. Most Venetian-era structures have been lovingly restored, including Chania's lighthouse and arsenals, as well as Heraklion's Loggia and city walls. Despite challenges posed by centuries of earthquakes and modern urban development pressures, wandering through an old Cretan town remains like stepping back in time. One moment you might be admiring a Minoan ruin on the outskirts, then pausing at a Venetian gate, catching the echo of a muezzin's call from a lone minaret, and finally enjoying a modern café tucked inside an ancient stone building. This layered architectural narrative is what makes Crete so captivating for both the architecture enthusiast and the casual visitor alike.